Rwandans jump to

faith they view as tolerant

|

By Laurie Goering

Chicago Tribune foreign correspondent

Published August 5, 2002

Reprinted from the Chicago Tribune online

KIGALI, Rwanda -- Long

before the call to prayer begins each Friday at noon, Rwanda's

Muslim faithful jam the main mosque in Kigali's Nyamirambo

neighborhood, the overflow crowd spreading prayer rugs on the mosque

steps, over the red earth parking lot and out the front gate.

Almost a decade after a

horrific genocide left 800,000 Rwandans dead and shook the faith of

this predominantly Christian nation, Islam, once seen as a fringe

religion, has surged in popularity.

|

Women in bright

tangerine, scarlet and blue headscarves stroll the bustling streets

of the capital beside men in long white tunics and embroidered caps.

Mosques and Islamic schools are overflowing with students. Today

about 14 percent of Rwandans consider themselves Muslim, up from

about 7 percent before the genocide.

|

"We're everywhere," says

Sheik Saleh Habimana, the leader of Rwanda's burgeoning Muslim

community, which has mosques in nearly all of the country's cities

and towns.

Countries around

Rwanda--Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda--have large Muslim communities. But

the religion never was particularly popular in Rwanda until the 1994

genocide, which spurred a rush of conversions.

From April to June 1994,

militias and mobs from the country's ethnic Hutu majority hunted and

murdered hundreds of thousands of ethnic Tutsis at the government's

urging. Within a few months, three of four Tutsis in the country had

been hacked to death, often with machetes or hoes. More than 100,000

suspected killers eventually were jailed.

|

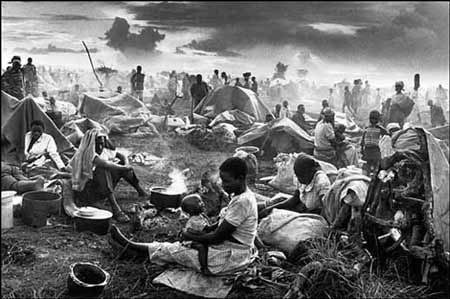

Rwandan

refugees in Tanzania in 1994, after the genocide.

The genocide stunned

Rwanda's Christian community. While clergy in many communities

struggled to protect their congregations and died with them, some

prominent Catholic and Protestant leaders joined in the killing

spree and are facing prosecution.

Elizaphan Ntakirutimana,

the head of Rwanda's Seventh-day Adventist Church, is on trial,

charged with luring Tutsi parishioners to his church in western

Kibuye province, then turning them over to Hutu militias that

slaughtered 2,000 to 6,000 in a single day.

The day before the

massacre, Tutsi Adventist clergy inside the church sent

Ntakirutimana a now-famous letter, informing him that "tomorrow we

will be killed with our families" and seeking his help. Survivors

report that he replied: "You must be eliminated. God doesn't want

you anymore."

Muslims offered haven

At the same time,

Rwanda's Muslims--many of them intermarried Tutsi-Hutu couples--were

opening their homes to thousands of desperate Tutsis. Muslim

families for the most part succeeded in hiding Tutsis from the Hutu

mobs, who feared entering the country's insular Muslim communities.

Yahya Kayiranga, a young

Tutsi who fled Kigali with his mother at the start of the genocide,

was taken into the home of a Muslim family in the central city of

Gitarama, where he hid until the killing was over. His father and

uncle who stayed behind in Kigali were murdered.

"We were helped by people

we didn't even know," the 27-year-old remembers, still impressed.

Unable to return to what

he considered a sullied Roman Catholic Church, he converted to Islam

in 1996. Today he is studying Arabic and the Koran at a local

madrassa and most mornings awakens for the dawn prayer, the first of

five each day.

His job as a money

changer in downtown Kigali conflicts with Islam's prohibitions on

profiting from financial transactions, but he thinks he has mostly

adapted well to his new faith.

"I thought at first Islam

would be hard, but that fear went away," he said. "It's not easy at

the beginning, but as you practice it becomes better, normal."

Rwanda's Muslim leaders

have struggled to impart the importance of unity and tolerance to

their converts, who number as many Hutus as Tutsis.

Reconciliation at

mosques

|

Habimana is one of the

leaders of the country's new interfaith commission, created to

promote acceptance, and in a country still seething with barely

masked anger and fear after the mass killings, Rwanda's mosques are

one of the few places where reconciliation appears to have genuinely

taken hold.

"In the Islamic faith,

Hutu and Tutsi are the same," Kayiranga said. "Islam teaches us

about brotherhood." |

Muslims

in Kigali, capital of Rwanda

While Rwanda's ethnic

Tutsis mostly have come to Islam seeking protection from purges and

to honor and emulate the people who saved them, Hutus also have

come, seeking to leave behind their violent past.

|

"They all felt the blood

on their hands and they embraced Islam to purify themselves,"

Habimana said.

Becoming Muslim has not

been an easy process for many Rwandans, who chafe at the religion's

dress and lifestyle restrictions. Despite Islam's new status,

Rwandan Muslims traditionally have been second-class citizens,

working as taxi drivers and traders in a society that reveres

farmers.

|

Muslim

women in Rwanda

"Because we were Muslim

we weren't considered Rwandanese," Habimana said. Now, as the

religion's popularity grows, that is changing.

Today "we see Muslims as

very kind people," said Salamah Ingabire, 20, who converted to Islam

in 1995 after losing two brothers in the killing spree. "What we saw

in the genocide changed our minds."

Below is a separate but

related article:

Rwanda Wakes Up

To Islam

Islamic

Voice, December 1999

Kigali (IINA): The Muslim

Association of Rwanda is doing everything possible within its means

to help new Muslims in learning more about the faith they have

chosen, and the practices that are enjoined by it, such as

circumcision, the eating of Halal food, the mode of dress, and other

related matters. Islam entered Rwanda in 1901, through Arab

merchants, and then from 1908 there followed several waves of Muslim

immigrations during the period of German colonisation of the

country. The first mosque to be built in Rwanda was built in 1913.

But it was not easy for Islam to spread in Rwanda, because there was

no studied plan for such work to be done, and the successive

colonial powers did not make matters any easier. For example, the

first Muslim school was built in 1957, but was confiscated by the

authorities, though it was returned to the Muslim community in 1997.

Rwanda gained its independence in 1962, and though the new rulers

recognised Islam as such, there still are stumbling blocks that were

and are being put in the way of the educational advancement of

Muslims in the country, and the image of Islam as such is very much

distorted.

However, things took a

different turn after the 1995 civil war that led to the death of

more than half a million Rwandans, but in which the Muslims had not

taken any part. From that time the picture of Islam in the minds of

the Rwandans took a 360 degrees turn, and from then on the

authorities in the country started to allow Muslims to expand their

propagation activities and to teach Rwandans about Islam.

Source :

http://www.zawaj.com/editorials/rwanda_islam.html |